Manitoba's mystery stonefly

An example of a classic spring. Tufa spring, Fort Ellice, MB (Photo by NCC)

Everyone enjoys a good mystery, even entomologists. During my early years of teaching a course in aquatic entomology at the University of Manitoba, the name Capnia manitoba kept appearing in the list of stoneflies in the province. It was a stonefly shrouded in mystery. It was known only from one location in Manitoba: Aweme, a mecca for Canadian entomologists.

C. manitoba had not been recorded in the province since its original description by P.W. Claassen in 1924, though it was known to occur widely in eastern Canada and the United States. Why hadn’t it been seen since 1907, when the specimens had been collected? Was it still in Manitoba? There is no suitable habitat in the immediate vicinity of Aweme (southwest of Brandon). Where had the specimens actually been found? These simple questions led to a fascinating journey that involved several people, took us into some of the most curious aquatic habitats in the province and exposed some basic human shortcomings. But first, some background.

What are stoneflies?

Stoneflies are an important group of aquatic insects living mostly in running water, where the greater part of their life cycle is spent in and on the substrate. Eggs are laid on the surface or under the water, where they hatch and develop through a number of immature stages, gradually increasing in size with each moult. The last aquatic stage emerges from the stream and crawls out onto surrounding objects. The winged adult emerges after one last moult. The life cycle usually lasts underwater at least one year, but some of the larger species in Manitoba can spend two or more years as nymphs.

Among the stoneflies, there are two unusual families, called “winter stoneflies.” Adult winter stoneflies emerge in March and April in Manitoba, sometimes when streams are still covered in ice. The adults of some species can be found crawling across the snow. They mate and the eggs are then laid in the water, where they sink to the bottom and hatch later in the season. The first-stage nymphs burrow deep into the substrate, becoming dormant for the entire summer and into the fall. By late fall, these nymphs return to the substrate surface and undertake the greatest portion of their growth during the cold winter months.

Tracking down a mystery stonefly

P.W. Claassen described C. manitoba based on a series of seven males and seven females collected in Aweme by Norman Criddle on April 28, 1907. The Criddle family lived in Aweme, where, in 1915, Norman established the first Dominion Entomology Laboratory, called St. Albans, near their home. The nearest present-day known localities for C. manitoba are hundreds of kilometres to the east, and this species had not been seen since Criddle’s original discovery.

I had wondered about the original collection location of this species for several years, when Dave Burton began his graduate research in our department. He enrolled in my advanced taxonomy course. Part of the requirements for the course was to undertake a research project. He was interested in stoneflies, so he decided to compile records for the stoneflies of Manitoba. Because the timing for the course was quite flexible, he spread it out to allow time to collect specimens from many additional locations.

Diving deep to solve Criddle's riddle

We tackled the C. manitoba issue in the early stages of the project. The question was: How to find out where this species had been collected? I spent many delightful hours with historian Alma Criddle, scouring Norman’s field notebooks, looking for clues. It became apparent that Aweme occupied a much greater conceptual area than just the immediate area around St. Albans. However, there was no solid evidence in the field notes for where Norman had been or what he collected that day in 1907.

When in doubt, go to the maps. Dave and I pulled out all the relevant topographical maps (no Google Earth in those days), poring over every detail. We soon zeroed in on a series of tiny squiggles along the east bank of the Assiniboine River, not far from Aweme. These squiggles are small springs that drain into the Assiniboine River, and what seemed to us at the time as ideal habitat for C. manitoba.

We undertook our first field trip at the end of February in 1982. Because there was no ready road access, we took skis to cross the fields. You can imagine our surprise when we reached the first large punchbowl spring, with steep sidewalls down to a broad spring seep, with large areas of open water. We had naively thought we could make our way to the site and just use our nets to collect the waiting stoneflies. Groundwater emerges at about 5 Celsius, so the entire area was unfrozen and access on skis was impossible. It had never occurred to us to take boots. We returned home to plan our next, better-informed and better-equipped trip. At least having seen the springs, we convinced ourselves this was the place we would find Capnia manitoba.

C. manitoba discovered at last

We returned to the springs closer to the date when Norman Criddle had collected adult C. Manitoba — in our case, April 22, 1982. We explored the first large punchbowl spring, a habitat choked with introduced watercress. To our disappointment, we did not find the stoneflies we were looking for. However, there were numerous small spring streams draining into the Assiniboine River. Here is where, at last, we found adult C. manitoba; lots of them. Mystery solved.

These beautiful stoneflies were flying actively along the margins of the springs on that sunny April afternoon.

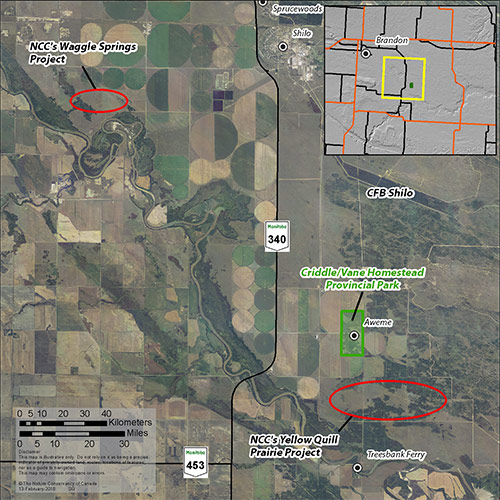

It was an eventful day, and we returned the following March to confirm that nymphs were present in the springs. There are, without doubt, many similar locations along the Assiniboine River where this rarely collected stonefly might occur. There is no inventory of springs in Manitoba. However, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) has recently completed an inventory of springs along the Assiniboine River, including the Waggle Springs properties, not far from Aweme. To my knowledge, no one has made a concerted effort to record the highly specialized aquatic invertebrate fauna that lives in a habitat where the temperature remains about 5 degrees Celsius all year long.

Aweme's location in relation to NCC properties (Map by NCC)

Mystery solved, but there's more work to be done

Armed with NCC’s inventory, it now should be possible to systematically visit each of these springs to survey not just for the presence of C. manitoba, but for other spring specialists as well. Springs are extremely susceptible to disturbance. Once the fauna in a spring is extirpated (no longer present in that particular spring but still living in other springs in the region or elsewhere), the original inhabitants may never return. Capnia manitoba (now Capnura manitoba) is one extraordinary species that lives in these springs in our province.

It was great fun to research and retrace the footsteps of one of Manitoba’s preeminent entomologists, and to solve a mystery that aquatic entomologists had been looking to solve for decades. There is an opportunity to discover many other new facets of life in springs in Manitoba.