Stopping the sixth extinction needs to start at home

Blanding's turtle (Photo by Gabrielle Fortin)

I can still remember the day I saw a Blanding’s turtle for the first time. It was at Point Pelee National Park, in Ontario, in 1990 while working as co-op student studying rare plants. I thought it was an amazing animal, with its high, domed shell and yellow chin. A warden told me it was a rare sight, as there were fewer in the park each passing year. It made me feel sad to think that such an incredible species could disappear from Point Pelee. What I didn’t know then was that this turtle was not just rare in Point Pelee and in Canada, but it was rare throughout its range and at risk of being lost forever.

Halting the rapid loss of species is one of the greatest conservation challenges we all face. We’re currently witnessing what has been called the “sixth extinction.” From birds to bumblebees, many species are declining. There are now fewer species on Earth than just a generation ago. Past mass extinction events were caused by massive volcanic activity and asteroids hitting the Earth. Today, our global trust of plants and animals is slipping away because of habitat loss and fragmentation, unsustainable use, climate change and invasive species.

Hitting close to home

Canadians often think about the species extinction crisis as something that’s happening elsewhere. The plight of elephants, tigers and gorillas is well known to many Canadians. We absolutely need to save these species, but stopping the global extinction crisis needs to start at home.

Whooping crane (Photo from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services/Flickr)

Canada is home to approximately 80,000 species, but at least 16 species and sub-species are now extinct — gone forever from Canada and from the planet. Some species you may have heard of, such as the passenger pigeon and great auk. The extinction story of others, such as the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, Macoun’s shining moss and deepwater cisco, are equally tragic, but not as well known.

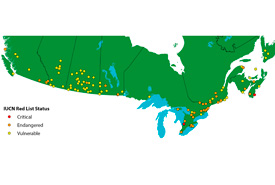

The global status of species is assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and maintained on its Red List of Threatened Species. Experts assess species based on criteria such as population, size of range and threats. Threatened species are then categorized as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable, depending on their level of extinction risk.

Currently, Canada has 179 species on the IUCN Red List. These include rare species with few individuals, such as whooping crane and north Atlantic right whale, but also species that are rapidly declining. In 2017, four ash species found in Canada were listed as critically endangered because of their rapid decline as a result of the invasive emerald ash borer. In addition, another 106 species have been assessed as near threatened in Canada, meaning they are likely to become endangered in the near future.

Western prairie fringed orchid (Photo by NCC)

Stepping up to the plate

One of the most important results of our conservation work at the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) is that we’re protecting and recovering more than 50 species on the IUCN Red List, or those that have been assessed as near threatened. Many of these species are on lands that were secured through the previous Natural Areas Conservation Program (NACP), a joint partnership between NCC and the Government of Canada. Under the NACP, NCC and our partners conserved more 1.1 million acres (more than 446,000 hectares) coast to coast, providing habitat for 210 federal species at risk. This year, another federal partnership called the Natural Heritage Conservation Program launched and continues the momentum of the NACP.

Protecting species across Canada

This investment is benefitting many species that are at risk of global extinction. In Manitoba’s tall grass region, NCC is protecting and restoring habitat for the western prairie fringed orchid (endangered) and Dakota skipper (vulnerable). In Atlantic Canada, NCC is protecting habitat for boreal felt lichen (critically endangered). Our conservation efforts are also protecting habitat for Sprague's pipit, cerulean warbler, rusty blackbird, Bicknell's thrush and long-tailed duck (all vulnerable).

Red-headed woodpecker (Photo by D. Fast)

Our work for near threatened species is important; it will hopefully help keep these species off the Red List. In Ontario’s Rice Lake Plains, northeast of Toronto, we’re restoring black oak savannah habitat that supports the red-headed woodpecker. In Atlantic Canada, NCC is protecting key habitat for piping plover and semipalmated sandpiper.

There’s something especially satisfying about our work protecting habitat for Blanding’s turtles. Since I first met a Blanding’s turtle as a student more than 25 years ago, NCC has protected thousands of acres of its habitat in places such as the Frontenac Arch and the Ottawa Valley; places where NCC will continue working to ensure its protection for the long term.

Map by NCC

Species from the IUCN Red List (September 2017) on NCC properties across Canada. Click to enlarge. (Map by NCC)

Perhaps of all our projects at NCC, it’s these conservation projects of globally threatened species that give me the deepest satisfaction about the legacy we will leave behind. We’re not just protecting species that are often threatened in Canada, but doing our part to halt the sixth extinction. Conserving these species is not only important for Canada, but important for saving life on Earth.