Tomorrow never knows: The importance of conserving the present to prepare for the unknown future

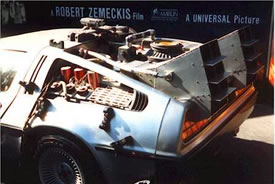

The modified De Lorean of the BttF movie (Photo by Wikimedia Commons, Cowboy Wisdom)

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow…

I love to watch reruns of the Back to the Future films every so often. Not just because I am a big fan of Michael J. Fox. But also because the future as envisaged in 1989’s BttF Part II, which seemed so distant when I first watched it as a young girl, is just around the corner. It’s funny to compare what director Robert Zemeckis thought 2015 would look like — hoverboards, smart clothes and flying cars — with reality.

Tomorrow: it can be exciting to think that those images of advances in transportation, health care, and communication — once the stuff of science fiction — are becoming science fact. When you work in the business of conservation, there is much uncertainty about the world to come. With an increasingly changing climate and species extinctions on the rise, it is more and more difficult to predict the future of the natural places we are conserving and all that lives within them.

There are ways to give nature a fighting chance, despite this uncertainty. The first of these, and perhaps the most important, is to work at scales large enough to allow species to move and adapt across the landscape as weather patterns and the climate transform. Landscape-scale conservation is most likely the best insurance against rapid and unpredictable change.

On the other hand, there is much that is fascinating and inspiring when we think about tomorrow. So much of that is also applicable to conservation—in part, because the challenges of tomorrow will be addressed through innovations in technology and our evolving understanding of the natural world. Conservationists now use tools and technologies that would have been unthinkable several decades ago. Property areas were once calculated with string on a map, and the fax machine was our most advanced means of communication. Now remote sensing, GPS, and computer modelling, in addition to complex databases, have made it easier to map and track landscapes and species.

Although the conservationists of tomorrow probably won’t be riding hoverboards through protected lands, they will continue to use the latest science and technology to conserve landscapes and provide safe passage for wildlife. But no matter what the advances, the principles that guided the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s founders more than 50 years ago — to take direct, private action to protect natural spaces and the species within them — will continue to inform the work of Canada’s leading land conservation organization.

Whether the future is approached with trepidation or inspiration, tomorrow is what we here at NCC think about on a regular basis — it’s what anchors our work. When we protect an acre of land today, we are already looking to tomorrow to forecast what might impact that land. And we are dreaming of the days when our children and grandchildren can stand in the places we have protected , breathe clean air and drink clean water.

This post originally appeared on The Walrus blog on February 20, 2014.