A prescription for forest health

Plantation rows in Southern Norfolk Sand Plain, ON (Photo by NCC)

When you think of a healthy, thriving forest, do you think of a straight lines of trees, all the same size, all the same species?

Probably not.

While tree plantations can be economically important and can provide significant ecological benefits compared with other types of non-natural landcover, they don't support the same rich biodiversity as natural forests, woodlands or savannahs. Those plant communities have many different species of tree, at all different ages, growing in organically occurring patterns, rather than uniformly aged trees in grid-like rows.

Within the Southern Norfolk Sand Plain (SNSP) Natural Area of Ontario, there is a long history of plantations, many of which were planted to prevent soil erosion following the clearing of forests by European settlers. At the time, plantations were a very important ecological restoration tool. However, a large percentage of these plantations are made up of non-native, invasive species, such as Scotch pine, or the locally non-native red pine.

Scotch pine seedlings taking over a restored field (Photo by NCC)

There is now a wider understanding that non-native species can create ecological issues. Large plantations of non-native pines can act as a seed source, creating huge numbers of seedlings, which quickly take over nearby meadows and prairies. If the non-native pines are not removed, these meadows and prairies will turn into pine monocultures and lose their biodiversity as well.

Part of the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (NCC's) long-term conservation work in SNSP includes conducting management work in plantations to transition them to more diverse, natural habitat.

In 2019, Brett Norman, NCC’s invasive species manager, and I systematically reviewed all the plantations on NCC lands in SNSP and developed long-term priorities for management and naturalization. We looked at a variety of considerations, including the size, estimated age and species, their location and species-at-risk locations. The management work would be a huge undertaking and so we split the plan up into multiple years of work.

In 2020, I set to work to begin the first year of the plan we created. Focusing on the highest priority plantations, I worked with registered professional foresters, local species-at-risk experts and local NCC staff with extensive forestry expertise to conduct site visits and inventories of the plantations.

Our collaboration allowed the foresters to create forestry prescriptions. Similar to how a doctor prescribes a specific treatment — such as diet, exercise or medication for a patient to improve their health — a forester can prescribe a specific course of action to improve the overall health of a forest. In this case, to improve the health of the forest and adjacent communities, part of the course of action we needed to take was removal of the non-native, invasive species.

Justin Olivera, OTS Contracting, with forestry feller buncher equipment (Photo by NCC)

Once the prescriptions were finalized, the appropriate permits were in place and the timing was right, the on-the-ground work began. A skilled local contractor used specialized machinery to carefully remove the invasive pine trees, while leaving native trees in place.

I worked with the contractor to point out places to put down tree tops and branches to create habitat for reptiles, small mammals, birds and insects. Although it might "look messy" to have branches and small logs scattered on the ground, this creates fantastic spots for wildlife to nest or rest in. Over time, the wood will break down and return nutrients to the soil, similar to what would happen if the tree fell naturally.

After forestry management in Southern Norfolk Sand Plain, ON (Photo by NCC)

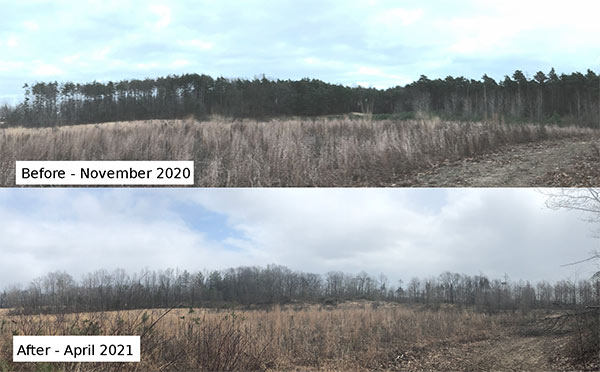

The first year of plantation management work took place over the winter, to minimize disturbance to the ground since it was frozen, and wildlife since fewer species are active during the winter. The following spring, the results were amazing to behold! After the non-native pines were removed, the native deciduous trees, which had been slowly establishing in the plantations, suddenly had no competition for sunlight and nutrients. The native trees took off! Since sunlight was now better able to reach the forest floor, native wildflowers and shrubs sprung up everywhere.

Before and after plantation management at Four Oaks Trail, Backus Woods, ON (Photo by NCC)

Although it might seem a bit unusual for a conservation organization to remove trees, in this case and in many others, it’s a necessary prescription for the health of the forest and surrounding ecosystems.