Nature's medicine

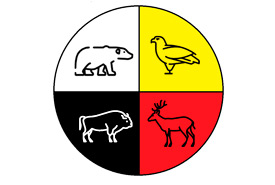

Medicine wheel (Image by NCC. Icons designed by Freepik from Flaticon)

As a Kanien'keha:ka (Mohawk) woman, my connection to my culture and my community is as important to me as the water I drink and the air I breathe. I find my Indigenous roots in nature, where my identity is as deep in the land as the roots in the cedar trees that line the forest by my house in the suburbs.

Living in a mid-sized city and commuting into Toronto for work, it’s sometimes hard to stay grounded in my Indigenous world views. During the week I am surrounded by pavement and rushes of people, and dictated by a busy work and social schedule. In these hectic times, I turn to the medicine wheel to find balance in my physical and mental well-being.

Medicine wheels, a circle shape often depicted with four quadrants, represent the interconnectivity of one’s being. Each quadrant, illustrated by a different colour, represents a different aspect of Indigenous life — from direction to medicines found in nature, from life stages to species found on Turtle Island.

These species may differ between cultures and individuals, but I grew up knowing them as bear, eagle, deer and bison.

Related blog posts

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) protects land across this nation for many species, including the ones found on my medicine wheel. In the face of climate change, protecting habitat for these species has never been more important than now. Learn more about these species and the threats they face, below:

North: Bear

Polar bear (Photo by Andrew Derocher)

While there are several bear species that live here, my favourite of the bunch is polar bear. Not only is the polar bear the biggest bear species, it’s also the world’s largest land carnivore. Males can weigh up to 800 kilograms and reach lengths of up to 2.8 metres, while females can weigh up to 400 kilograms and reach lengths of up to 2.5 metres.

Polar bears are found throughout the Arctic in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Norway and Russia. In Canada, they inhabit ice-covered regions from the Yukon and the Bering Sea in the west, to Newfoundland and Labrador in the east. They also range from Northern Ellesmere Island south to James Bay.

Two-thirds of the global population of polar bears are found in Canada. The world’s southernmost population of polar bears occurs along the coast of James Bay in Ontario.

Polar bears face many threats, including climate change, contaminant exposure, resource industry activities and conflict with humans. In the long term, climate change is the most serious of these threats. The effects of climate change have critically impacted the amount and thickness of sea ice, decreasing polar bears’ primary habitat for hunting seals.

East: Eagle

Golden eagle (Photo by NCC)

There is nothing more majestic than an eagle flying overhead across a cloudless blue sky. The golden eagle is one of the biggest and fastest birds of prey in North America, with a wingspan of up to two metres and the ability to dive at speeds of over 240 kilometres per hour.

While their preferred habitat is open country near mountains, hills and riverside cliffs, golden eagles are found in a variety of habitats, ranging from the Arctic to the desert. Although they usually nest on cliffs, they also do so in trees, on the ground and on human structures, such as telephone poles. Not all golden eagles migrate, but most in northern and eastern Canada usually fly south in the fall.

In Ontario, golden eagles are listed as endangered. This species is threatened by the accumulation of toxic chemicals or lead from ammunition, collisions with vehicles, wind turbines and other structures, as well as electrocution from power poles.

NCC protects several properties across the country where golden eagles have been observed during their breeding season and migration. Many of these properties are large, connected tracts of natural habitat, which provide the basic necessities for these large predators.

South: Deer

Mule deer (Photo by Allison Haskell)

Some of my favourite memories in nature involve walking through thick forests lined with trees and shrubs and catching a glimpse of a mule deer grazing or taking a drink of water.

Mule deer are one of several species that rely on healthy habitats, such as grasslands and forests, to survive. Grasslands are in extreme decline. There are many reasons why grasslands are endangered in Canada and around the world.

Globally, grasslands are faced with continuing habitat loss, fragmentation and desertification. These impact both hte biodiversity of grasslands and the people who rely them for their livelihood. More than 50 per cent of the world’s temperate grasslands have been converted to crops and other land uses. Much of what remains is intensively grazed by livestock; they replaced what were some of the planet’s greatest concentrations of wild grazing animals, such as plains bison.

West: Bison

Plains bison (Photo by Steve Zack)

While I’ve never had the chance to see plains bison roam freely across prairie lands in real life, I’m often taken back to the painting my grandfather had over his chair that illustrated a herd feeding with their young.

A symbol of determination and indomitable spirit, bison are distinguished from other cloven-hoofed ruminants by their massive woolly heads, curved black horns and forequarters. They are North America's largest land mammal and can grow to be two metres tall, weighing more than 900 kilograms. Despite their size, bison are surprisingly agile: they can reach speeds of up to 60 kilometres per hour, turn faster than a horse and jump almost two feet straight up from a standing position.

In the early 1800s, an estimated 30 million to 60 million wild plains bison roamed the continent, but by the turn of the century over-hunting had decreased their numbers to less than 300. As settlers headed west, close to 70 per cent of Canada's original grasslands were converted for agriculture or other purposes.

Since reintroducing the species to its native habitat in December 2003, NCC has continued to manage a herd of genetically pure plains bison at the Old Man on His Back Prairie and Heritage Conservation Area in southwestern Saskatchewan. The herd currently numbers about 100 animals.

I hope to one day share my medicine wheel with my children. I will teach them about the land and, while doing so, I hope to be able to catch a glimpse of an eagle spreading its wings above or see a deer between the tree stands. Humans, wildlife and the land are all connected. Together we can protect land for these four species and for our children and grandchildren to enjoy.