Pushing petals: Exploring Canadian botanical art

Illustration by Raymond Nakamura

Summer has turned to fall, as the pandemic blurs the days. If you are able, please stay at home. But remember that you can still go outside and enjoy some nature, while maintaining a safe distance from others. Plants can provide a nature-based outlet for creativity during these troubling times. As experiences become more virtual, we thought we’d share some botanical art to bring nature to you.

The famous physicist Richard Feynman recalled an argument he had with an artist friend regarding their differences in how they perceived nature. The artist friend thought that science took away from the appreciation of the beauty, while Feynman felt science could only add to it.

The term "botanical art” refers to art “whose goal is to depict whole plants or parts of plants in a manner that is both aesthetically pleasing and scientifically accurate,” according to the Botanical Artists of Canada. With traditions in both Europe and Asia, botanical illustration has a long history reaching back to the Common Era, when plants had to be identified and recorded for medicinal purposes without a globally recognized taxonomic system or the convenience of camera phones and identification apps.

But there are many ways to create art involving botany. Here are some artworks that demonstrate the range in how artists work with and portray plants, from traditional botanical illustration to using real plants:

Western fairy orchid, watercolour on paper (By Vicky Earle; used with permission)

Orchids have a reputation for being exotic, but many orchids can be found in Canada, including the western fairy orchid, which artist Vicky Earle has depicted wonderfully in watercolour.

“They are tiny jewel boxes on six-inch stems. I continue to be mesmerized by the intricate shape of their blossoms and also the range of their colours: violets, pinks, maroons, and gold. Even the stems have an interesting structure and pattern,” Vicky says. “And their story? Fairy orchids rely on ‘pollination by deception’ by attracting insects, usually bumblebees, with a sweet aroma, but provide no nectar as a reward. Their corms were also used as a food source and medicine by First Nations in British Columbia. Gorgeous, devious and useful. What more could you ask for in a plant?”

For a seasoned homebody, it was a dazzling experience to spot some fairy slipper orchids on a mountain hike in Alberta. And it was equally dazzling to see Vicky’s portrayal of the same orchid in a botanical art exhibit in Ottawa. It certainly speaks to the skill of botanical artists that they depict plants with such realism that the art might be mistaken for the real thing.

“From an artistic point of view, the diversity of shapes, patterns, colours, functions and textures that plants offer us is astounding — yet many people barely notice them,” says Vicky. “I love creating botanical art to highlight the beauty of plants and tell the stories of their key roles within larger ecosystems and cycles.”

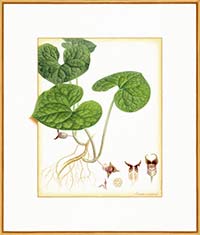

Asaret du Canada / Canadian wild ginger (By Lilyane Coulombe; used with permission)

On top of the beautiful cross-sections and leaf venation, what we appreciate in Lilyane Coulombe’s illustration of wild ginger is her use of the frame.

“I like to play with volume to render a three-dimensional effect. Painting part of a leaf outside of the frame creates the impression that it’s coming towards us,” says Lilyane. “As for wild ginger, I was fascinated by the texture of the leaves created by the complex pattern of its ribs. The flowers of Canadian wild ginger are hidden in its leaves, but they deserve our attention. When the flower starts to open, the reflection of its stamens creates a delicate pattern. After several hours, the anthers spring up and free their pollen.”

Botanical illustration provides surface information, but there’s so much more to a plant.

“While I travel the fields, the woods, the riverside in search of specimens, I make extraordinary discoveries and I throw myself into a true adventure. Guided by curiosity, I contemplate, I admire, I marvel, I get drunk! It’s a little like I’ve entered into communion with the plant,” says Lilyane. “Little by little, I observe the variations in colour, the multiple veins, the transparency of the fruits, the delicate petals. I discover the tricks that the plants had to develop to adapt, the strategies they had to use to spread their seeds to promote dispersion.”

Plants are capable of such astonishing variation, strategies and movement, but these are not as widely known as their appearance. Lilyane’s work reaches out and invites viewers to discover more about the plants she portrays.

Shooting star (By Gerard Brender À Brandis; used with permission)

Woodcut is an old printmaking method. The artist, or engraver, essentially draws by carving a reverse image into a block of wood, then applies a layer of ink and stamps it onto paper. It has a romantic touch to it because the transfer of the image is like a kiss from one part of nature to another.

Gerard Brender À Brandis is one such wood engraver. His botanical work, tinted (hand coloured) or untinted, is like something plucked from a beautiful, drug-addled dream.

“I understand that shooting star is rare in Canada, possibly limited to southern Manitoba, but much more common in the U.S. I have drawn it a number of times from a plant that I bought from a nursery specializing in native plants and grow in my garden,” says Gerard. “I love flowers with swept back petals, cyclamens, Narcissus cyclamineus [cyclamen-flowered daffodil], dogtooth violets, Turk’s cap lilies (though I resent it in some orchids such as miltonias) but cannot explain why.”

Gerard’s sentiment is a familiar one. Without knowing their names, people can fall in love with flowers and their supple petals, delightful fragrances, and strange variations.

Canada mayflower, wet plate collodion ambrotype (2014) (By Julya Hajnoczky; used with permission)

Julya Hajnoczky, an artist of many talents, uses wet plate photography to portray plants in a haunting way, with veils of leaves and skeletal stems. It recalls the early cyanotypes of Anna Atkins and broadens the way plants are recorded.

“The ambrotypes and rayographs that I’ve made of plants tend to function almost like x-rays, revealing intricate structures, along with evidence of the life history of the plant evidenced in bug bites, weak spots, flowers or berries, and so on,” Julya says. “These analog processes in particular are very ‘true,’ in the sense that they are physical records of actual plants. My aesthetic or artistic contribution lies in the selection of a specimen and the composition of the image, but not in altering the plant physically or later, digitally.”

She also composes images that reveal the bigger picture: “Most of the work I create aims to reproduce or represent the very fine details of the specimens that I work with. With my high-resolution scans, I’m trying to put humans and specimens on the same scale, making prints where pine cones or lichens are the size of a human, and I also try to create compositions that are a portrait of a specific ecosystem.”

Such images remind us that plants in the wild are not solitary but are tightly interconnected with other plants.

Forget-me-nots (By Laara Cerman; used with permission)

Sometimes an artistic representation can’t stand up to the real thing. Modernizing the record-keeping of plants is Laara Cerman. In her ongoing series, Codex Pacificus, she arranges and scans wild plant specimens.

She recently started to bring her scanner and laptop into the forest, scanning plants without removing them from their ecosystem. To obtain a scan in the field, she uses black velvet to darken the area surrounding the plant, inverts the scanner (so the glass is face down), and flattens the plant just enough against the glass to capture an image. She then improves the quality of the image with Photoshop.

“There are some plants I’ve learned are better not to pick, such as Trillium ovatum, which apparently takes years to grow from seed!” Laara says. “It was also this flower that made me want to try scanning in the field. I’d like to capture rare and parasitic plants, which I will need to do in the forest as I don’t believe it’s right to remove them.”

Laara’s arrangements teach us about each plant’s identity, and her evolving techniques and new works will remind us of the wildness the plants inhabit.

For inspiration, and to learn more about botanical illustration, check out Botanical Artists of Canada. The Botanical Art & Artists website provides technical tips for trying your hand at botanical art.

And no matter how you decide to enjoy nature, take care of yourself.

This post was written by Katrina Vera Wong and Raymond Nakamura, multimedia editors with Science Borealis, and is reposted with permission. It first appeared on Science Borealis’ blog.