Something’s Fishy: Living like salmon

Fish jumping over a cascading river (Photo by Drew Farwell, Unsplash)

As part of my identity journey and reconnecting to my Haudenosaunee culture, I’ve been slowly learning Kanien'kéha. Every morning, I start the day with a cup of coffee, and several open tabs on my computer filled with text and audio recordings of this beautiful language spoken by my ancestors. Without someone to teach me, it’s the best I can do.

I try to learn one word a day and, to hold myself accountable and maybe inspire others to do the same, I share that word on Twitter. I’m in no way a teacher or expert in this language, but, like many other Indigenous Peoples who grew up without their traditional language, I have to start somewhere.

Related content

For me, this journey started with one word: kontihnawa:ra.

Atlantic salmon are an anadromous species, migrating from salt water to fresh water to spawn. (Photo by Hans-Petter Fjeld)

Kontihnawa:ra, which means “salmon,” has been a catalyst for many things in my life — from my studies to my inherent love for Mother Earth. From early memories of fishing with my grandfather, to studying salmon and its cousins in labs at Fleming College, to my first summer job spent catching, measuring and releasing fish for surveys and now, as I continue to reclaim this language, salmon has been a guiding force in my life.

Like salmon, I’m no stranger to swimming upstream. I look to this fish as a metaphor: the more difficult and challenging a journey is, the more triumphant and fulfilling the end goal feels.

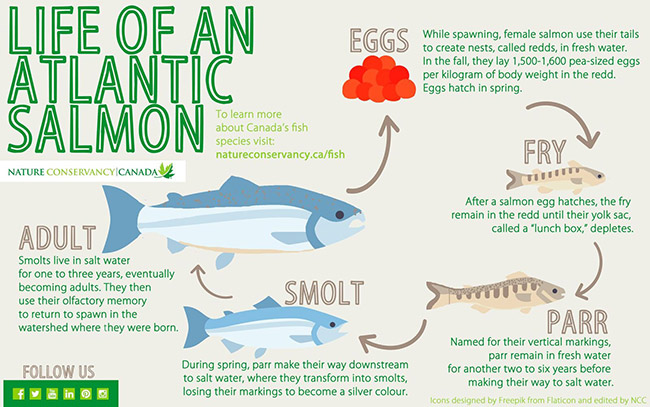

Like humans, salmon undergo different life stages and will take many voyages throughout their life cycle. Although shorter-lived than the average person, these fish — specifically Atlantic salmon — constantly adapt and transform during their life cycle.

Atlantic salmon smolts (Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Hatched in rivers, newly hatched salmon are called alevins. After two years, they grow into smolts and change into a silvery colour as they prepare to migrate to salt water. This stage of their life begins in the fall, but the actual migration occurs in late May or June. After one to three years at sea, smolts mature into adult salmon.

Their diet changes as they develop, too. Juvenile salmon still living in their native river eat zooplankton and invertebrates. As they migrate to salt water, their diet changes. In the ocean, salmon consume herring, krill and shrimp.

Unlike the salmon’s diet, traditional diets within Haudenosaunee communities have remained largely unchanged. Fish were and continue to be an important part of Haudenosaunee culture and diet. Fishing was traditionally done by men, who used nets and spears to bring in fish to feed their community. They also used hooks and lines for fishing; seeking out lakes, rivers and streams for this important food source.

Salmonier River, Avalon Peninsula, NL (Photo by Mike Dembeck)

As I learn more about myself and about salmon, I further understand the idea that we are all related, and we have an obligation to take care of one another. In December 2015, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) began Phase 2 of our conservation efforts on the Salmonier River in Newfoundland and Labrador. This involves conserving an additional two properties along the river, totalling 176 hectares (436 acres). The Salmonier River is a provincially designated salmon river, hosting a healthy population of Atlantic salmon. To date, NCC has conserved 64 hectares (158 acres) here.

We protect water for salmon, and, in turn, they provide us with nourishment. This reciprocity continues to inspire and connect me not only with the land, but with the cultural roots my family has deep within it.

While I’m still just a smolt in terms of my language journey, the more I learn about my culture through the traditional Kanien'kéha language, the closer I swim toward the reclamation of my identity.