Canadian Federation of Humane Societies Conference 2014

One method to address domestic cat overpopulation issues is a trap-neuter-return solution (Photo by Sajin Nijas)

This year, as an outside but complementary interest to my work with the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), I was fortunate enough to attend the 2014 Canadian Federation of Humane Societies conference (CFHS) in Toronto, Ontario. The conference hosted a variety of participants from a wide range of sectors, from animal shelters to government, the veterinary community, universities and nature conservation organizations.

We were very fortunate to have Jane Goodall, founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the UN Messenger of Peace, as a keynote speaker. While I attended several sessions on a variety of topics, I thought that I would share just a few that may be of interest to some our Land Lines readers.

Keynote speaker: Jane Goodall – Hope for animals

Having just celebrated her 80th birthday, Jane Goodall took to the stage to spread her message of hope for animals. Jane shared with us some of her experiences working under her mentor, famed anthropologist and paleontologist Louis Leakey, at the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve. She also shared some of the challenges and reflections about why the program became successful in the community and abroad.

Jane Goodall’s message of peace, love and empathy stretches beyond the animals she works with to the people and environment. One of the stories she told was of a chimp research laboratory where she was giving a guest presentation. Very much on the defensive, the researchers prepared themselves for a lecture on their poor practices and standards. Instead, Jane shared life experiences of chimps, showing videos and letting the audience get to know them as she had.

By getting into people’s hearts, she was able to open up a different point of view for these chimp researchers, inspiring them to come up with standards and practices to improve the animal welfare at their facility.

This type of philosophy, of educating and empowering people in communities, has helped boost conservation efforts, bring animals back from the brink of extinction in several parts of the world. Jane Goodall continues to be an inspiration. Her Roots & Shoots program (through the Jane Goodall Institute of Canada) aims to teach and empower the people of Uganda through partnerships with groups all over the world.

Using population models and trap-neuter-return address domestic cat overpopulation issues

The management of domestic cats can be a challenge but may include education campaigns directed to communities where people are encouraged to spay and neuter their cat and to keep them indoors, on a leash or contained in an outdoor enclosure. This may be effective with human-owned cats, however a significant number of the domestic cat population is located in non-owned feral cat colonies.

In some areas, usually where human populations are concentrated, cats (whether human-owned or feral) pose a threat to birds such as ground nesting bird species like the piping plover. To address cat overpopulation issues, one is the practice of trap-neuter-return (TNR). TNR involves live trapping, neutering and releasing animals back into a managed population where a volunteer continues to care for the colony as a whole. In this way, it is thought that individual cats can maintain rank and structure within the colony while not continuing to reproduce.

It is hoped that in the long term, TNR can help stabilize and decrease overall domestic cat populations, removing some of the burden from shelters and indirectly also reducing predation on suffering bird populations.

In addition to managing populations sizes, TNR programs may also be an effective and humane solution that avoids euthanasia, which is often a very difficult and emotional task for shelter workers.

While volunteer groups attempt to manage population size through coordinated spay/neuter and TNR programs, other researchsers are asking questions about the best approach, technique and effort required to achieved desired results that will effectively stabilize a population.

Tyler Flockhart, population and conservation biologist at the Ontario Veterinary College and University of Guelph, is conducting a study that aims to improve domestic cat welfare, reduce growth and population size, move towards “no kill” policies and promote effective interventions such as TNR. Using population viability analysis (a method used in conservation biology typically used to assess threats a species at risk may face and evaluate long-term survival), Flockhart hopes to develop a model to predict population dynamics and examine the effectiveness of TNR type interventions. One key question the study will seek to answer is whether TNR decreases cat population size over time.

Should TNR type programs prove to be successful at managing feral cat colony populations, we may see a coming together or at least an area of common ground between the cat and bird issue debate, at least in areas where habitats containing threatened species overlap. Perhaps we may even see partnerships develop between conservation groups, animal welfare and government to support TNR type programs.

The relationship between human and animal welfare

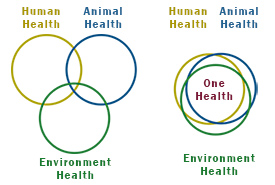

Another intriguing session included a presentation from Ontario veterinarian Dr. Michelle Lem, who introduced the concept of One Health, One Welfare. The model subscribes to the concept that we are all connected. To have a healthy society as a whole, we need to care for humans, animals and the environment (see accompanying graphic, below).

One Health, One Welfare concept

Using pet ownership as an example, Dr. Lem discussed the issue of who should or could own a pet when comparing the overall income of homeowners versus a homeless person’s financial capacity.

Although many people can benefit from pet ownership, it is sometimes thought that homeless or disadvantaged people should not own a pet as they are not able to properly afford to take care of them. While this may be true in some cases, it is also true that many people living with a modest or even higher income may not be able to afford to care for a pet, once debt load enters consideration.

In fact, a study of street youth has shown that in most cases the overall health of pets owned by homeless people are in much better health and have fewer behaviour problems than typical homeowners’ pets since the homeless spend more time with their pets while obtaining an increased levels of exercise.

Homeless people also benefit greatly from pet ownership, as they may experience increased social interaction, bonding and companionship. Many people will go to great lengths to look after their pet, as they may be the only source of love and security in their lives.

Dr. Lem and her team have come up with their own way to contribute to the One Health, One Welfare concept. They have devoted some of their time and resources to help disadvantaged people in the community care for their pets. Not only does the group at Community Veterinary Outreach Program help to cover costs associated with preventative vet education and care, but through referral, they are also able to have meaningful discussions and help guide people to vital human health community resources including mental health care programs and facilities. The clients are so grateful for any help and generosity given to them on behalf of their beloved pets that they are more open and willing to also help themselves in the process.

To help animals and the environment, we must not forget to help people

As is the case in many areas of helping the environment or animals, we sometimes forget that we also need to help the people in the communities. As Jane Goodall can attest, some of the most successful conservation and welfare approaches occur when we help the people in a community. This can mean providing economic stability, education and understanding as well as accessible health care to a region. In turn, this can mean that direct reliance on or overuse of valuable resources is reduced or replaced.

The ability to help animals and the environment was one of the main reasons that I came to work for NCC over six years ago. NCC continues to work in collaboration with communities every day to create and maintain special places that allow biodiversity to thrive and people to enjoy nature's health and spiritual benefits when connecting with animals and the environment.