Common ground conservation

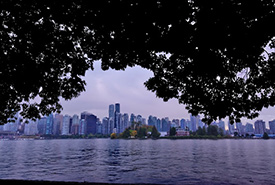

Downtown Vancouver (Photo by Adam Hunter/NCC staff)

We’re currently running one of the world’s biggest experiments. You’re part of it, and I’m part of it. For the first time in the history of modern humans, we’ve attempted to detach ourselves, and our children, from nature. For 99.9995 per cent of our shared human history, we lived in close contact with nature. We intimately knew the plants and animals around us. We had dirt under our fingernails. We stared in the eyes of other living things before we ate them. We knew that we were a part of nature.

In the last few generations, our Canadian population has shifted from a nation of busy farmers, fishers and loggers to a nation of screen-staring urbanites, with over 80 per cent of us living in cities. This urban migration is happening around the world. The great ape that walked out of the African savannah over 60,000 years ago and spread across a global wilderness and conquered nature, now sits in buildings around the world.

Unfortunately, our experiment in separating humanity from ecology is failing nature, and failing people.

In the brief history of this land as the nation of Canada, there has been some great progress in protecting and connecting with nature. Canada now has protected almost 12 per cent of our lands and inland waters. The Nature Conservancy of Canada has protected almost 3 million acres (more than 1.1 million hectares), thanks to support from thousands of Canadians. Kids have the opportunity to learn about almost any species or habitat with a few clicks on a keyboard.

But despite all this, nature is still losing ground. While there are some positive trends, the overall health of all major Canadian habitats is declining. This loss of habitat has had a big impact on our wildlife. Our Canadian list of wildlife species assessed as at risk (of extinction) is continuing to grow, doubling in less than 20 years.

As we lose nature and our connection to the natural world, it’s not just habitats and rare species that are at risk. We are also at risk of losing the benefits that nature provides. Although the modern world provides much that improves our lives, our disconnect from nature is compromising our human condition. There is a growing list of society’s nature withdrawal symptoms: attention-deficit, depression, reduced creativity and empathy, cardiovascular disease, allergies and asthma. These mind and body responses to our new nature-light lifestyle are real, and they are measureable.

Wetland in Beaver Hills, AB (Photo by Beaver Hills Initiative)

But here’s a secret: while modern society can make us feel disconnected from nature, this is a dangerous illusion. We are ultimately as dependent on nature as our ancestors. Wetlands clean our drinking water, forests store carbon, which stabilizes our climate, insects pollinate many of our crops, floodplains reduce the impacts of extreme weather events and, globally, wildlife is part of a multi-billion dollar industry that supports local economies and brings joy to millions of people.

While we may have replaced pelts with plastic, and fire with fission, we have not developed a substitute for clean air, water and food. Nor have we developed a substitute for the sense of wonder that being in nature can spark.

Related blog posts

So, the big question is, “Can we redefine our relationship with nature?” As individuals, as corporations, as government and society? Can we make the changes that will protect species and habitats, and protect the services and well-being that nature provides to people now and in the future?

I think the answer is yes. The answer needs to be yes, and I want to tell you why I have hope. Part of this hope is rooted in history. Our relationship to nature has always been dynamic; it’s always been changing. There are things we did in the past that would never occur today.

For over 200 years, waterfowl, shorebirds and seabirds were a commodity in North America. They were hunted without limits. A report from Cape Breton in 1750 notes that up to 1,000 gunshots occurred every day in the spring, as gunners targeted birds as they migrated along the coast to nesting colonies on islands (1). While Indigenous peoples had harvested seabirds sustainably for thousands of years, a new era of commercial hunting for adults, chicks and eggs threatened the existence of many bird species.

In 1970, 12 members of the southern resident killer whales’ L-pod were rounded up off the coast of BC and Washington. Seven of the whales captured were sold to marine parks around the world. Five of the captured whales drowned. Killer whales (back then known as blackfish) were misunderstood and hated by many people. The federal government even had a mounted machine gun overlooking Seymour Narrows, northwest of Campbell River, to shoot at them in 1961.

Pod of orcas (Photo by Robin Agrarwhal CC BY-NC)

Why did these things change? We recognized we were surpassing limits, and we recognized the costs to people. The risk of losing migratory birds concerned a growing number of birdwatchers, hunters and other citizens a century ago. We have developed an enhanced empathy for wildlife — especially marine — mammals in the last 50 years. Selling orcas as an amusement show commodity, or shooting them, not only offends our current values but also risks a booming whale-watching industry.

Not everyone wanted to make these changes. There were institutions built around the status quo. But change happened. In 1916, Canada and the U.S. signed the Migratory Bird Treaty to stop the indiscriminate and commercial hunting of birds. Not only did laws change, but our entire hunting culture transformed. Killer whale populations in BC were first protected in 1970 under the Wildlife Act, and in adjacent U.S. waters in 1972 under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

These were very complex problems. They involved science, politics, economics and social values. But somehow, they found common ground. They found solutions. These past changes to our relationships with nature required vision and bold action. Vision and bold action that benefit us here and now.

We don’t have a commercial harvest for birds like Atlantic puffins or semipalmated sandpipers anymore. Today, people line the beaches with binoculars, not guns, to witness the annual migration of shorebirds. Today, we have laws that protect marine mammals, and our entire value system has changed. We don’t sell orcas, we now empathize with a mother orca as she pushes her dead calf, and we try to give killer whales medicine when they are ill.

Atlantic puffins (Photo by Laurel Bernard/NCC staff)

Those past actions are almost unthinkable. Today we are protectors of orcas and puffins. To my kids, this will seem normal, but hidden in history is that this normal required a monumental shift in our relationship with nature.

There is still more that we need to do to help populations of marine mammals and many species of birds, to reduce plastic waste and stop climate change. But the greatest threat to nature in Canada is habitat loss. If we continue to lose habitats, we will continue to lose wildlife. And we will continue to lose what nature provides to us, and what nature could provide to our children.

Stopping habitat loss; this is the vision and bold action we need today. This is the challenge for our generation, and the challenge of our lives.

What will the next chapter be in our evolving relationship with nature? In this age of the Anthropocene, our human influence is everywhere. We need to choose, and in many cases choose quickly, what we save, and what we lose. We need to choose what future generations will have, and what they will have not; what can be touched, and what can only be remembered.

Everyone benefits from protecting nature. These are places of wildlife, places of wellness and diverse economies, places of our Canadian identity, places of wonder. In protecting these places, there is common ground for everyone.

Finding that common ground starts with a relationship, with the spark of connection. By knowing what we all gain when we protect nature, and what we risk if wildlife and wild places continue to slip away. Discovering, knowing and sharing your relationship with nature is critical.

Connect with nature. The connection will change you. And you can change the world.

This blog post is based on my 2018 NatureTalks presentation. NatureTalks will be held again this year. For more information, click here.

1. Mowat F. Sea of slaughter. 1st American ed. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press; 1984. 438 p. p.