Something's Fishy: The legendary lamprey

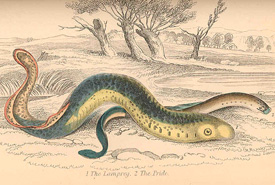

The Lamprey, 2. The Pride, 1866 (Illustration by Robert Hamilton)

Anyone who knows me could tell you I’m really into folklore. Fairy tales, spooky stories and legendary accounts of people, places and mystical things have intrigued me for as long as I can remember. I'm also really into fish. So if there is a legend about a fish, you can bet I’ve heard it.

That’s why I was surprised when I came across the tales surrounding an ancient fish species, more than 300 million years old, which I’ve seen swim (some might say slither) in Ontario waters.

In folklore, lamprey are referred to as "nine-eyed eels." This name is derived from the seven external gill slits that, along with one nostril and one eye, line each side of a lamprey's head. The German word for lamprey is Neunauge, which when translated means "nine-eye."

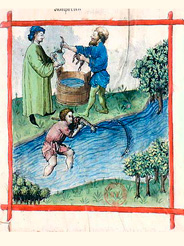

In ancient Rome, Vedius Pollio, an equestrian and friend of emperor Augustus, was punished by his imperial comrade for trying to feed a clumsy slave to his lampreys after he dropped a crystal cup in a pond. Contrary to this story, lampreys do not eat humans; but they do have a thirst for blood.

Medieval European depiction of fishing for lamprey from Tacuinum Sanitatis, 15th century (Illustration from Wikimedia Commons)

To other fish species, lampreys are like underwater vampires. Although they have no bones or jaw, their mouths are shaped like a funnel lined with tiny teeth. This enables them to latch on to other fish and slowly suck their blood, leaving the lamprey’s prey defenceless while it eventually succumbs to its captor.

The bodies of lampreys are smooth and scaleless, ranging from five to 40 inches long. They have large eyes on either side of their head, with a single nostril in the centre. They are able to breathe using external gill slits that, like the folklore suggests, look like little holes or eyes. The absence of pectoral fins gives the species a snake-like appearance, similar to freshwater eels — a species for which they’re commonly mistaken.

Atlantic sea lamprey (Photo by T. Lawrence, Great Lakes Fishery Commission)

In Canada there are 11 species of lamprey swimming in waters across the country. One in particular has been causing trouble, especially in its non-native waters.

Despite always living in Lake Ontario, the Atlantic sea lamprey is considered invasive to the Great Lakes. First making its way into Lake Erie in 1921, it is said the species entered through the Welland Canal. By 1940 it was fully established throughout the Great Lakes.

Atlantic sea lamprey have cylindrical bodies and no scales. They are grey to dark brown with darker blotches and light undersides. This species feasts on large fish species and has contributed immensley to the decline of whitefish and trout.

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission was created between Canada and the United States in response to the devastating impact of the Atlantic sea lamprey on Great Lakes sport, commercial and Aboriginal fisheries in the 1940s and 50s — a problem that still exists today. Although complete local extirpation is highly unlikely, there have been ongoing efforts to combat the spread of this species.

But lampreys aren’t invasive everywhere. Despite the havoc the Atlantic sea lamprey has caused in the west, it is considered native to the Atlantic coastline and considered imperilled in Newfoundland and Labrador’s waters.

Like the sea lamprey, the chestnut lamprey is a parasitic species. Located in select Saskatchewan and Manitoba rivers, this species will latch onto its prey for food. The chestnut lamprey mates only once between the ages of seven and nine years old. During this time individuals will ditch their usual grey-olive colour for a blue-black shade. After they mate, spawn and lay their eggs, adult chestnut lampreys will die, leaving the young to fend for themselves.

Also residing in Saskatchewan waters are silver lamprey. There are two separately recognized populations of this species in Canada: one in the Great Lakes in the Upper St. Lawrence and the other in Saskatchewan’s Nelson biogeographic areas. Due to the threats from the invasive sea lamprey, the species is considered a species of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

Sharing the waters with the silver lamprey is the nonparasitic northern brook lamprey.

Mouth of an Atlantic sea lamprey (Photo by T. Lawrence, Great Lakes Fishery Commission)

Northern brook lamprey reside in Ontario, southwestern Quebec and southeastern Manitoba and are distinguishable from other Canadian lamprey species by their size, fins and teeth. The species is much smaller than the silver lamprey, with a single dorsal fin and unique teeth pattern. Pre-spawning females may sport an orange-tinted belly from visible eggs waiting to be laid.

Considering the northern brook lamprey is, what one could say, a fish of many lakes, I was surprised to find out its western look-alike was so restricted in its range.

In Canada, western brook lamprey, also known as Morrison Creek lamprey, are found only in the Morrison Creek watershed in Courtenay, BC. Their limited range increases the species’ vulnerability to threats such as changes in the water quality and levels and human impact in the area. COSEWIC lists the western brook lamprey as endangered.

Similarly, lake lamprey are confined to a small distribution region.

Vancouver lamprey, known simply as lake lamprey, is blue-black or dark brown with light undersides. This species has two dorsal fins, a small caudal fin and a low anal fin and can be as long as more than two feet. This species of lamprey can only be found in the Cowichan and Mesachie Lakes on Vancouver Island, BC. According to scientists, this limited distribution is due to glaciation patterns from the last Ice Age.

Similar to chestnut lamprey, lake lampreys only breed once in their lifetime (May–August) when they are about eight years old, but don’t die after laying their eggs. Although they only spawn once, they appear to lay a high number of larvae that help sustain the species.

Since lake lamprey have a limited distribution, they are more susceptible to habitat degradation; much like the western brook lamprey. According to COSEWIC, this species is considered threatened. Any negative alterations to water quality or a decrease in food sources would jeopardize the species. They rely on the availability of juvenile coho salmon in Cowichan Lake, whose population has been in an ongoing decline. This is expected to a have a significant impact on lamprey numbers.

There’s no doubt about it: lampreys are an incredibly interesting species. I sometimes sit and think about the hot July day with the sun in my eyes and when I spotted what I could have sworn was a snake in the water — my first glimpse of a lamprey. Although my admiration for the species does not rival that of Lucius Licinius Crassus, known to have wept over the death of his pet lamprey, they still hold a special place in my fish-loving heart.

Something’s Fishy is a monthly series written by NCC’s Communications Assistant, Raechel Bonomo, highlighting a species or group of fishes that inhabitant Canadian waters.