The plants we leave behind

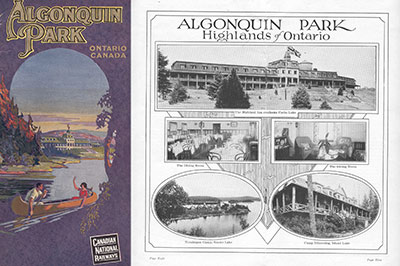

1925 Canadian National Railways Algonquin Park pamphlet showing painting of Highland Inn on cover, with centerfold photographs of Highland Inn, Nominigan Camp and Camp Minnesing (Public Domain)

Nominigan Camp in Ontario’s Algonquin Park was built along the shore of Smoke Lake in 1913. During its peak, the log cabins and main lodge could host almost 100 guests. It later became a private residence and was abandoned and dismantled back in 1977.

Today, there’s not much left. You could easily paddle along the shore and think this land is untouched. Trees have returned where log cabins once stood. If you are inclined to search, you will find moss-covered concrete steps and an eye hook embedded in the rock by the shore. But there’s a much more obvious sign of its former presence.

Sedum (Photo by Dan Kraus/NCC staff)

You can tell by the plants.

Scattered in the woods and along the shore are the plants that the people from Nominigan Camp brought to this place. Goutweed, carpet bugle, sedum…even if you’re not a botanist, they are probably recognizable. These are familiar plant names to many people because they occur in yards and parks across Canada.

There were probably more plants here that the people of Nominigan Camp brought. Without human care, they have perished. But goutweed, carpet bugle and others survived and even thrived when their keepers left.

Eye hook embedded in the rock by the shore (Photo by Dan Kraus/NCC staff)

You can find the plants that have been left behind in many places. They are clues to the past. A patch of lily of the valley in the woods probably means there is an abandoned homestead nearby. A line of Norway spruce once planted as a windbreak can be all that’s left to outline an old farm laneway. One of the reasons I am so intrigued by plants is that they are like a time machine; they provide a window into the past and a glimpse of future ecosystems. Of what a place was, and what it will become.

Some of the plants that we once tended in gardens may change the future of our natural habitats. At Nominigan Camp, goutweed has broken from its garden bonds and spread into the woods. There are many Nature Conservancy of Canada properties across the country where we are managing species such as periwinkle and Japanese knotweed that also long ago escaped from gardens. These invasive plants can spread and invade natural habitats. Left unmanaged, they will change the composition and function of local ecosystems and displace our native plants and the wildlife that relies on them.

Old steps that led up to the lodge (Photo by Dan Kraus/NCC staff)

More and more, people are playing a central role in the distribution and abundance of plant life. But humans have been leaving a botanical footprint for millennia. We’ve moved plants around the world for food, fodder and fashion. In Canada, Indigenous Peoples transplanted and tended plants, such as pawpaw, Saskatoon berry and wild camass, and this has influenced the distribution of these plants today. Indigenous Peoples also managed the composition of local plant communities, such as the tallgrass prairies of Ontario's Rice Lake Plains and Garry oak ecosystems in BC. Indigenous communities’ caretaking of the land enriched the abundance and diversity of their native flora.

Looking at goutweed along the shores of Smoke Lake makes me think about the plants that I will leave behind.

Most of us know and grow the same plants in our gardens, regardless of where we live. Walk down a suburban street in Toronto or Tofino, and you’ll see many of the same flowers and shrubs. Increasingly, it appears that our collective botanical legacy will be a homogenization of plant life — a floristic franchise that is stealing our knowledge of place.

But there is a different floristic footprint we can leave to the future. Canada has about 4,000 native plant species. While our richness and diversity of plant life is under threat, there remain pockets of our native flora even in the places where most Canadians live. Vignettes of ecosystems that are adapted to the local environment and define the places we live. Aspen parkland in Edmonton, black oak woodlands in Toronto and Acadian forests in Halifax can all provide inspiration about a different relationship with plants. One where nature informs and inspires us about what to grow.

In our current state of planetary problems, it can be easy to think that people are always a threat to nature. But we can also be stewards. We can seek wisdom in Indigenous practices. We can each take small acts of conservation in the places we live. The result of our time in our place can be a richer diversity and abundance of life.

We can start with the plants that we grow and will leave behind.